In 1932, Indiana Governor Harry G. Leslie tasked Col. Richard Lieber, the first director of the Department of Conservation, with helming the Indiana Commission for the Century of Progress Exposition. Wanting to depart from the typical state fair display of threshing machines and farm produce, Lieber proposed a 250-foot mural showcasing state history.

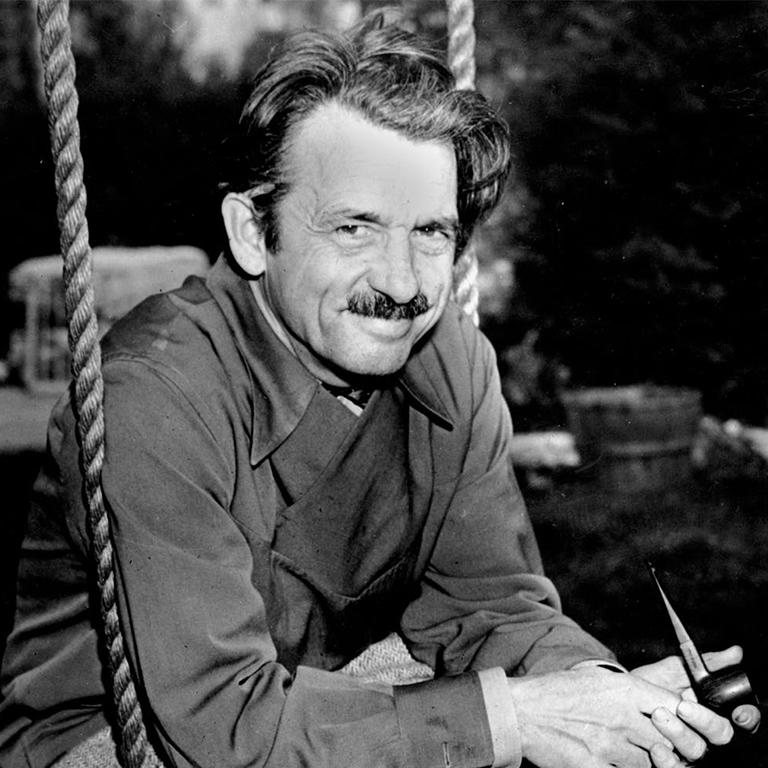

The contract went to relative unknown Thomas Hart Benton. The muralist asked for complete artistic freedom on the job, including the composition of the overall narrative and the realistic treatment of social facts. His request was granted.

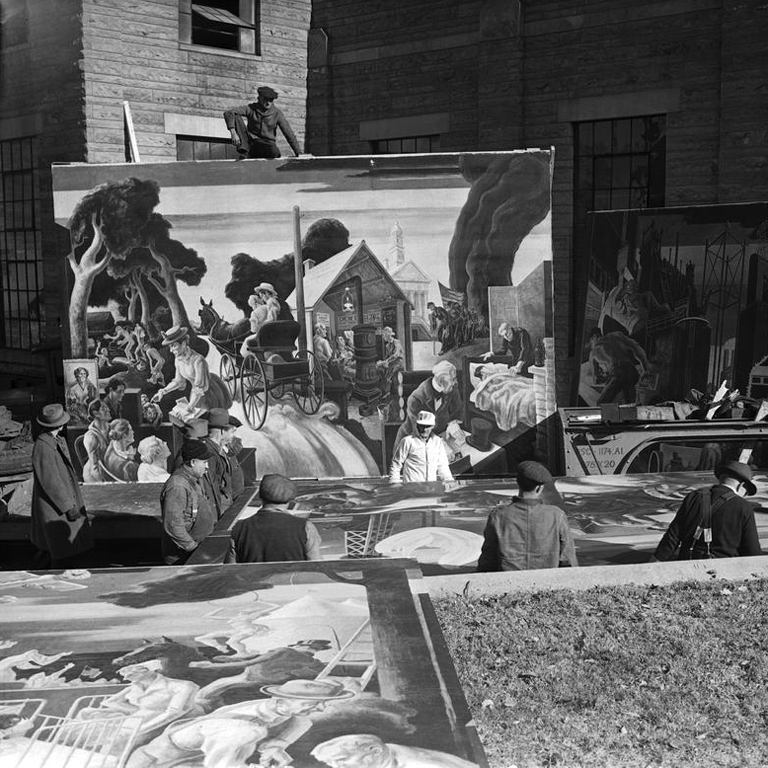

Once completed, the murals headed to Chicago. Benton was on site not only to survise their installation but also to paint a free-standing panel of the Indiana Dunes. This work has since gone missing.

Once completed, the murals headed to Chicago. Benton was on site not only to survise their installation but also to paint a free-standing panel of the Indiana Dunes. This work has since gone missing.